Thirty-two different shoe soles — heavy treading, youthful bounces, step patterns somewhere in between — all hit the ground at some point before night’s end to breach the boundary of inside and out. So many heads hit the hay here that, frankly, it’s too many; this house isn’t built for sixteen.

That fact alone doesn’t change a thing. 119 Beam Street is all they have left, and that, by default, makes it home.

At least it’s in Porter.

1940 — Kate Miller of 119 Beam Street in Porter, Indiana, at the very least, still manages to live beneath a roof in the town she knows like the back of her hand — the town where her children will grow up, where most of her living relatives still reside almost eighty years later — and this feat alone is some kind of blessing. At least in this house, now home to her mother, father, and all of her siblings, her husband and children, her sister’s husband and children, and, the bow on top, a paying boarder related to none of them… at least the backdrop rings familiar.

Still, amidst the noise, chaos, verifiable cacophony of a household this size, Kate cannot help longing for her last home, the first that really belonged to her. It was at 605 Franklin Street that she shed the Korytoski name when she married Frank Miller; it was there she became a mother. Not everything worth remembering was a mile-stone; some were just Sundays after church that have a neat glow to them in personal posterity, operations that seemed important at the time and look small in the distance, evenings with baby JoJo in her lap while Frank doodled some endearing cartoon on a wisp of paper.

Not even rose-colored glasses would let her recall that time as without worry — worries about house payments were justified, after all, since they darkly foreshadowed this elbow-to-elbow living situation — but a time without worry is not her heartfelt wish. She yearns, as earnestly as one can use the word, for space. A kind of metaphorical claustrophobia can develop even (or sometimes especially) around the closest of loved ones.

Catherine Margaret Korytoski, my great-great-grandmother, was born somewhere in Illinois on November 18, 1911. Even though the three generations of women that come between me and her are still around, I cannot find an explanation for Kate’s birthplace. She was the oldest of six, and all of the siblings that followed were born in Indiana. In the end, though, the state you are born in matters less than whatever place functions as home for you — for Kate, this place was Porter. Her family comes from Porter, and that she returned, as most do.

Porter is, generally speaking, more defined by loose area and conception than specific municipal boundaries. It is a smaller town within Chesterton, Indiana; confusingly, it is also the name of the county where these towns reside, and more confusingly still, the township of Chesterton that Porter can be found in is called Westchester, which spans more area than one, less than the other, and utilizes the ‘Chester’ stem that gets tossed around Indiana like it used to ride the tornadoes for self-preservation. A few things shape and characterize the ‘Porter’ I’m discussing — one school district, proximity to Lake Michigan and the Indiana Dunes, a history unified in family names and familiar landmarks. Mentions of Porter and Chesterton refer to this same community, as the social concept of the town is more important in our case than any formal delineation from local government. Porter is a community of overlapping history more so than one side of some train tracks.

Kate’s family (and thus, mine) is a part of this history. Her mother Helen was born a Janowski, a family name as wind-scattered through Porter as those Chester-stemmed town names are throughout the state. Helen’s father Adam Janowski owned a fair amount of property in Chesterton, and it was Helen among his many children who took care of him in old age. When her dedication to family was rewarded generously and somewhat disproportionately within her father’s will, her brothers demanded their fair share; Helen relented to this demand, forfeiting her claim to the money and land — and never spoke to her brothers again. This background story ties Kate’s family permanently to the land and community. Porter is the type of place you find yourself returning to even when you’ve fought estranged relatives over land in it, that spot you drive to when you get behind the wheel and start functioning on muscle memory alone.

Yes, Helen staying in Porter after this ordeal says something about what Porter is to its inhabitants, but the drama also culminates directly into Kate’s confinement to this home with so many others — cramped, crowded, and craving space.

Shifting houses is shifting lives. I have lived in at least 5 in my life, and every time a move impends, that’s a life on the precipice of being a new one. Yet the thought of shuffling around Porter does not inspire so much trepidation for me. Enough feels constant within the town to mark new homes as steadied by the other familiar attributes of life.

As painless as shifting houses within the realm of Porter seems, this relative ease causes its own problems. 119 Beam Street originally belonged to the Swedish side of the family, Frank’s parents Nels and Anna — ‘the Miller house’ as my mother calls it while she tries to piece together messy details of who lived where and when. I furiously fact-check alongside her to ensure that this version of the story, muddled through time and retelling, has retained some kind of accuracy despite being passed around and misinterpreted like a game of Telephone.

Though Frank was the one to bring this bigger house on Beam Street to the Korytoski family, he and Kate ended up at 605 Franklin, a house that belonged to Helen. It was a gift from her father — not part of the inherited land she had left in the hands of her brothers, but a piece of land he had bought and paid off for her while he was still alive. How, though, a reasonable person might wonder, did Frank and Kate end up in this Janowski house rather than the Miller one? While I tried to make sense of the stories my mother remembered, she kept returning to certain knowledge that someone had switched houses at Helen’s behest. Because the Korytoski household (Kate’s parents and siblings) had more people, the ‘suggestion’ came that they should live in the bigger house on Beam Street. Remembered for better or for worse as the matriarch to the family, Helen was not the kind of mother whose ‘suggestions’ went ignored. Things went the way she wanted them to, and her family lived at 119 Beam Street while the Millers staked claim on Franklin Street.

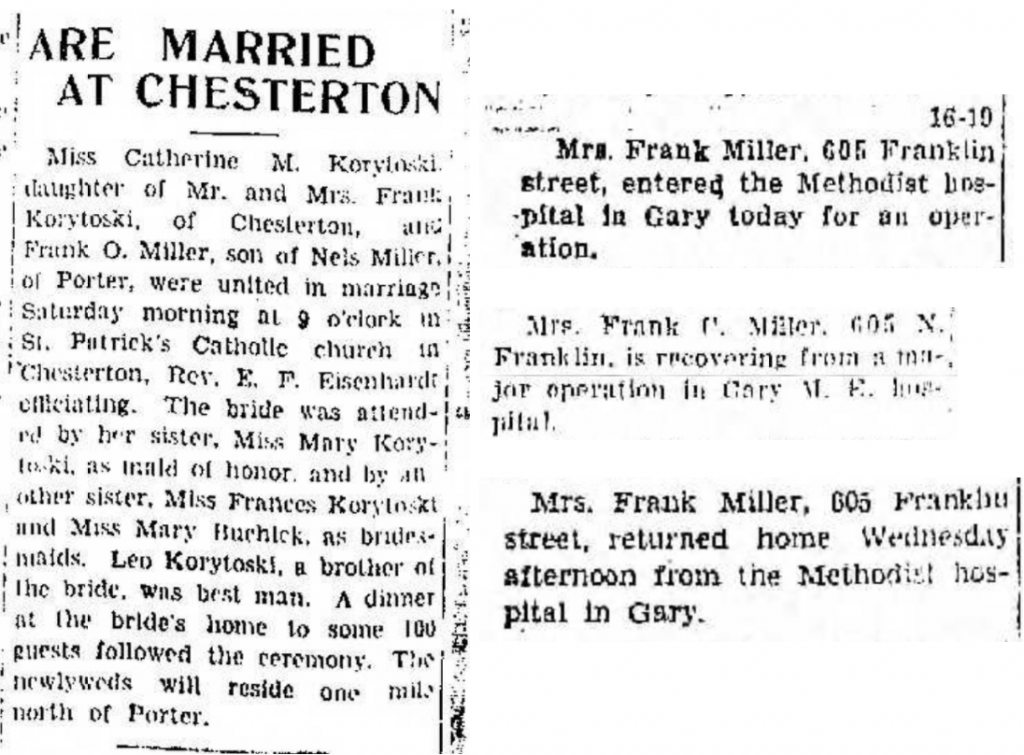

Everything fit together, but family agreements cannot always account for the demands of the world. Kate and Frank were married in 1934, and the impositions of life descended quickly. The local papers would scour personal events like the Miller wedding (see Fig. 1) for the finest of particulars; an article about Kate’s sister’s wedding outlines even more minor minutiae. Neighbors could learn without an invitation, for example, that “the bride [Mary] […] chose a lovely gown of green flowered crepe, with which she wore dark green accessories,” and that “[h]er corsage was of sweet peas and roses.” Other clippings (see Fig. 2) mention three separate updates on a surgery Kate had; including her home address and hospital indicates the level of (somewhat invasive, but perhaps charmingly so) detail in the Chesterton Tribune and Valparaiso Vidette Messenger. The area has changed, and so have the papers, but they are still small and often oriented to personal life in this way. I showed up in articles from the Chesterton Tribune three-quarters of a century later, and all I really did there was go to school.

The meticulous nature of the area’s papers fills an important gap in the story. The operation clippings tell us that Kate lived at 605 Franklin in 1934, but by the 1940 census, she is at Beam Street with the other 15. 119 is stuffed, filled to the rafters, standing room only, and what happened to her beautiful little house? The one where she could walk to visit her family whenever she wanted, not where she is, with nowhere to hide, surrounded by her own kids, her sister’s kids, all of her siblings down to Edward, her brother in the eighth grade — and a boarder to boot. My mom remembers a mortgage on some house, and one getting lost. Switching. There’s Beam Street, and one on 8th Street, but maybe that factors in later? It takes a while to make sense of it all, and the most depressing of my findings in the newspaper helps the most.

February 8, 1938, employment section of the paper: “WANTED—Work of any kind by capable man. Frank Miller.” And in the same issue, but the miscellaneous sales section: “GENUINE GIBSON Style A-4 Mandolin, also diamond Elks ring for sale. Frank Miller.” Though the Great Depression was ending in the historical sense, our historical concept of a time has no bearing on the reality for individuals. It was Kate’s reality in the late 30s that her husband could not find work. The 1940 census backs this up, noting that Frank worked for only 20 weeks during 1939. He was a house painter, and while his family’s memory of him now as something of an artist as well contributes more personally to his progeny, this skill did not protect the Millers from economic hardship. Frank had to look for any job he could, sell his belongings, and, as we now understand, take out another mortgage on the Franklin house, already paid off once by his grandfather-in-law, just to scrape by. In the end, as these things often go, and despite their best efforts, the Millers lost this house; gone was the little place that Kate could call her own.

For better or for worse, Kate is here on Beam Street, living not only with her husband and the three kids she’s had so far, but also her parents, five siblings, niece, nephew, brother-in-law, and boarder who is not related to any of them. Porter is what its people live, rather than lines drawn by the county; similarly, the Depression is in the late 30s for Kate, when she and Frank fret incessantly about losing their home, and in 1940, when that worst fear has come true, when their little family has been added to nearly a dozen other people. No matter when that worse fear comes, the next day follows, and you have to keep living.

So that’s what Kate does.

She and her sister Mary jointly assume the mantle of keeping house, and though it may not look like the life they pictured nor the life they had before the other shoe dropped, they do what women have always done: they make do. They clean and cook and take care of all the overlapping families in the house. They talk about things they like, things they would have if they could afford it, sending the little ones to school someday soon. They’ll make it happen. They’ll make do.

Even as money is scarce, they entertain. They learn card games that will come in handy to housewives in a few years, when they get back on their feet and can afford to host pinochle. They teach their sisters how to play, too. Franny and Margy won’t end up with the same kind of life, instead trading motherhood, marriage, and pinochle galore for independence and exciting experiences as Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service (WAVES) during World War II, but the time together certainly counts as sisterly bonding if not a transfer of necessarily useful skills.

Though she does not understand the motivation, Kate can’t bring herself to blame Franny and Margy for preserving their personal freedom. A couple years living in a sixteen-person household is enough to turn most away from that kind of responsibility, but even at her most frazzled and imposed on, Kate doesn’t wish away the family that relies on her. All she wants is a place to call their own. 605 Franklin is gone, but the vision is still there, and it draws her to act dutifully as a mother. When she leaves 119 for the day to recalibrate, she does so with her children in tow, pleading for Frank to go with them and finally getting her way. Another adult is useful to grab sticky, pudgy toddler hands and keep the babies attached from wandering, but Kate wants her husband to accompany them for more than that. This traipse across town serves as wish fulfillment; for even just an hour, Kate has her immediate family together as a private unit. Going in public to achieve privacy, while paradoxical, makes sense to her today.

When they reach their destination, Kate is aware of her now imposing stature. In a town where her feet are wider than the streets, walking through designated areas to preserve all the structures, she surveys a kingdom of buildings that barely reach her knee. With one hand shielding her eyes from the sun and the other wrapped instinctively, protectively around baby Margo on her hip, she spots Frank and the other two within her line of sight. Her gaze shifts instead to one cozy little house. Nothing is particularly notable about it, especially with showstoppers nearby like the tiny, functional train and a replica of the Neuschwanstein Castle in Germany; it attracts Kate’s attention anyway. Here, in the littlest town she could visit, “the only city in the US covered by insurance from just one company,” Kate feels more space than she ever could at home.

This is Littleville, a handcrafted collection of miniature buildings created by William Murray that managed to entertain thousands near the end of the Great Depression. A stalling economy, after all, can mean very little to children who still demand to be entertained. Littleville rests a few blocks from Chesterton’s main street, about a mile from the Beam Street house, and entry is only nickel — even in the Depression, even in the Miller’s own Depression, an affordable way to be entertained (Shook).

Nearby, another little town rattles on its hinges while two trains barrel past one another. Unlike Littleville, Porter is sized to be livable. Though it has been a source of stress for Kate lately, ultimately, it holds more than a day or two of touristy fun. If Littleville is somewhere to visit, Porter is somewhere to live.

Kate Miller — Ma Kate as I vaguely knew of her in my childhood — died on November 11, 1964. She has not been able to tell her own stories in a long time, and my mother, born in 1978, never met her. My grandmother and great grandmother, baby Margo, are both still around, so my younger self considered that to be the end of the line; I knew nothing of Kate, and I had no motivation to change that.

While I worked on this research, I stumbled upon the existence of Littleville. I asked my mom how I had lived in Chesterton for so many years and never heard of it. She told me, a little dumbfounded, that I had visited when I was little. One crumbled building was all that remained then (Overmeyer), and not even that is left today (Schultz). Though I was born in Chesterton, my family moved around often while I was in elementary school — I never felt like I was from anywhere. Things like having relatives in your class or family nearby weren’t something I experienced, but it never quite dawned on me how often those things did happen when I moved back. Almost 700 miles away at college, I realized that I did have a hometown, and a family history ingrained into it. The painting of Bugs Bunny on the side of the dry-cleaners that was removed when I was in high school was something Frank had done; that definitely explains why my mother was upset when it got painted over. Though my childhood memories aren’t filled with stories of Kate, we share some concept of home, and that’s something. We’ll make do. At least it’s Porter.

Works Cited

Overmeyer, Beverly. Only Rock Castle Remains of Littleville Today. 18 Sept. 2005, www.nwitimes.com/news/local/only-rock-castle-remains-of-littleville-today/article_49f3aae0-7c32-5a8c-8f8f-59416870c585.html.

Schultz, Jeff. “’Lost Tourist Attractions of the Dunes’ Exhibit Extending Its Stay Here.” The Chesterton Tribune, 20 Aug. 2010, chestertontribune.com/Local History/820101 lost_tourist_attractions_of_the.htm.

Shook, Steven R. “Littleville: World’s Biggest Little Village.” Porter County’s Past: An Amateur Historian’s Perspective, Blogger, 22 Dec. 2015, www.porterhistory.org/2015/12/littleville-worlds-biggest-little.html.

Various news clippings. The Vidette-Messenger, Valparaiso, Indiana, 1934-1938. Newspaper Archive Database.

Photo Sources

Photo 1:

‘Scene in Porter, Ind.’. Circa 1920s, postmark illegible. “Porter, Indiana – Street Scenes,” Historical Images of Porter County, Porter County, Indiana: A Part of the Indiana GenWeb Project, collected by Steven R. Shook, www.inportercounty.org/PhotoPages/Porter/StreetScenes/Porter-StreetScene005.html.

Figures 1 & 2

Various news clippings. The Vidette-Messenger, Valparaiso, Indiana, 1934. Newspaper Archive Database.

Photo 2:

‘Franklin Street: Porter, Indiana’. 1948. “Porter, Indiana – Street Scenes,” Historical Images of Porter County, Porter County, Indiana: A Part of the Indiana GenWeb Project, collected by Steven R. Shook, www.inportercounty.org/PhotoPages/Porter/StreetScenes/Porter-StreetScene003.html.

Photo 3

“Littleville, a Miniature Town, Chesterton, Ind’. Circa 1940s, postmarked 6 May 1952. “Littleville,” Historical Images of Porter County, Porter County, Indiana: A Part of the Indiana GenWeb Project, collected by Steven R. Shook, www.inportercounty.org/PhotoPages/Chesterton/Littleville/Chesterton-Littleville017.html.

Photo 4

“Hello! hello! Meet me vonce here in Porter already; good luck be mit you. Porter, Indiana’. 1916, postmarked 16 Feb. 1916. “Porter – Generic,” Historical Images of Porter County, Porter County, Indiana: A Part of the Indiana GenWeb Project, collected by Steven R. Shook, www.inportercounty.org/PhotoPages/Chesterton/Littleville/Chesterton-Littleville017.html.