“Hindi mo kailangang ipagparangalan ang mayroon ka. Hayaang magsalita ang iyong hirap sa sarili.” – “Don” Antero Abata Cartas

“You don’t have to flaunt what you have. Let your hard work speak for itself.”

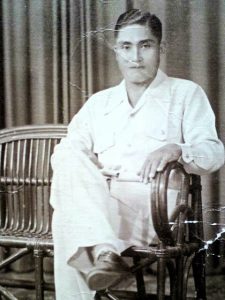

These types of dictums were preached in the Cartas household by my great-grandfather, Antero “Don” Abata Cartas. A man built by hard work and dedication, Antero spent his life working on the farmlands of the Philippines. Although he refused to flaunt his accomplishments, Antero established a dynasty that would flourish for generations and it all started in Ilocos Norte, Philippines. Once Antero met my great grandmother Fabiana Caburao they moved to Sual, Pangasinan, Philippines in the 1930’s and so began the man who became “Don.”

It’s 4 a.m. in Sual, Pangasinan, Philippines. The summer sun barely kisses the horizon as her rays begin to unfold across the sky’s canvas. Antero stretches his limbs, awakening his bones to prepare for the hard day’s work ahead and proceeds to work on his farm. Antero did not need a thermometer because there is only one word to describe the weather in the Philippines: hot.

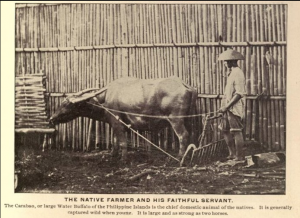

Antero grew various produce on his farm: nipa wood, rice, mango, and coconut. With the use of Philippine carabao’s and the first rice mill in the entire town, Antero expanded his farm so much he hired people to do the work for him rather than him doing it alone. The main tools that he used on his farm were carabao and a kariton (cart) or kareta (sled) made by nipa wood; since the Great Depression had a severe economic impact on America, Antero ensured that the tools he used were Philippine-grown and made to certify that only he was held accountable for any mistakes.

Although his farming techniques may have been simple and less mechanical, “The main features and benefits of traditional farming are to sustain the capacity of the soil to produce healthy and organic crops using available resources. This is the type of farming that prevailed in the Philippines before the introduction of mechanized and chemical farming” (Gomez 4). For example, my great-grandfather used a compost pit that not only kept his community sanitized by preventing disease and illness but it also led to a flourishing crop season. The same methodologies are still being practiced by Filipino farmers today. Maintaining an eco-sanitized environment was crucial for Antero because in the early 1900’s there was an unfortunate scare that carabao, the backbone of Philippine farming, would become extinct due to the rinderpest disease. Almost 90% of the Philippine carabao population were victims of the disease due to its consumption of infected vegetation (Roque 36). Fortunately, none of the carabaos were affected by the mass infection due to his hygiene practices.

After sending off his six daughters to climb three miles worth of mountains to get to school, Antero gathers his troop to assign them to their tasks for the day. Some would be in charge of plowing the rice, climbing the coconut tree to pick fresh coconuts, or even made a dessert from the nipa palm tree. The nipa palm tree was essential to the tradition that Antero instilled on his farm. Whenever his workers cut down a nipa tree and collect the sap that flowed from its veins, the first drop was used by women to make dessert. The second drop was used to make wine, and the final drop was used to make vinegar. Antero mainly wanted to help and serve the people, so the products that were made by his workers would often be sent home with them as a form of payment and appreciation for their hard work.

Not only could the nipa wood provide plows for the carabao but it also served as the structure for a family’s home. Referred to as a “Bahay Kubo” (cube house), this single-room elevated house provided shelter during monsoons: “Though the styles of the nipa hut vary throughout the country, most of them are raised slightly above the ground and one must enter them by means of ladders. Under the nipa hut, the Filipinos keep their swine, goats and fowl” (Alojado 1). Often times Antero would have his workers build their own houses out of his wood, and he even made his very own Bahay Kubo that still resides on his land, today. Yet, building an empire required Antero to dedicate his entire life to his farm and community and he moved from being a simple Filipino farmer to one of Sual’s most respected citizens.

Being recognized as an influential individual in Sual, Antero decided to allow his workers to maintain the farm while he ventured toward politics. Eventually, he ran for councilman in his town, which led him to be the highest ranking official in the city. While in his career he also served as a temporary vice mayor. “He always wanted to give back to the community” his eldest daughter Josefina recalls, “My father valued hard work and remaining humble. He taught me that you need to be happy about the simple things in life because that’s how the people in the Philippines are. Hard working and happy with what they have.” His community in Sual did not depend on American manufactured tools or goods to survive, they had to make their own and Antero knew that his people needed work. As his farm began to expand and miles of land are turned into acres, Antero decided to recruit local residents to work for him because fathers and mothers were struggling to find steady jobs that could support their family. His daughter Josefina mentions: “My father made use of everything that we owned. No food or tools went to waste. He even made us use the same two pencils for a year to teach us how to appreciate the small things that we own.” Josefina reflects about her father’s personality stating: “That’s why he made use of everything he owned because he knew that we were wealthier than most people and they would do anything to have the life we did”. Raising a family, building a community, creating a lifeline for future generations required Antero to live a life full of work but it was well worth it when he saw how successful his farm was.

My great-grandfather preached about letting your work speak for itself. Luckily it, paid off for him during the Great Depression. With the expansion of his farm and the need to grow more produce, he employed almost the entire town of Sual. Not only was he profiting from his produce but it was a way for him to reach out to the local community and provide them jobs that were scarce at the time. Antero utilized his land not only to his advantage but to the advantage of his people, he wanted to show his family that just because they were wealthier than their neighbors they were no better than they were. Wealth and fame did not hinder the vision that Don had for his dynasty, after all the farm that carried Sual on its back during the Great Depression is still standing today.

Works Cited

Alojado, Jennibeth Montejo. “From Nipa Hut to House of Stone.” From Nipa Hut to House of Stone – Philippine Islands, 8 Aug. 2012, web.archive.org/web/20120808001732/http://www.philippine-islands.ph/en/from_nipa_hut_to_house_of_stone-aid_21.html.

Gomez, Alexis P. “Plowing with Buffaloes in the Philippines – an Interview with One of the Photo Contest Winners.” Bioversity International: Research for Development, 21 Sept. 2015, www.bioversityinternational.org/news/detail/plowing-with-buffaloes-in-the-philippines-an-interview-with-one-of-the-photo-contest-winners/.

Roque, Anselmo S. “Carabao Rises to New-Found Importance as Farmers’ ‘Beast of Fortune’.” Philippine Carabao Center, 11 Sept. 2015, www.pcc.gov.ph/carabao-rises-to-new-found-importance-as-farmers-beast-of-fortune/.

Sison, Tiffany Josephine. “‘All About Antero’ .” 12 Mar. 2019.