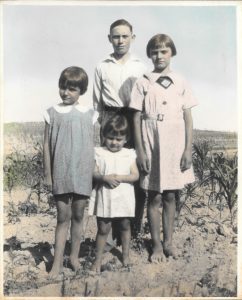

My maternal grandmother, Laura Jane Waldrop Gregg, did not coin the idiom “Waste not, want not,” but she lived it every day in the way she managed her house. Born in 1899 and married in 1921, she had her third of four children—my mother–in October 1929, just at the cusp of the Great Depression, and her fourth child—my aunt Dot–in 1933, in the heart of it. She and her husband, Henry Clay Gregg, owned a small farm in the Samantha community in rural North Tuscaloosa County, Alabama, where they grew corn, cotton, sugar cane, and field peas, and it was a daily struggle to hang on—to keep food on the table, to keep the kids in clothes and shoes, to pay the seed and fertilizer bills, to pay the mortgage, to survive.

I find it interesting that the McGraw-Hill Dictionary of American Idioms and Phrasal Verbs gives this example for “Waste, not, want not”: “Always save the fabric scraps left over you’re your sewing projects; you can use them to make something else.” This is exactly what my grandmother did. She saved and used every scrap to make warm quilts for her family . She pressed the scraps with a cast iron “sad iron” heated on a cast iron stove, folded them neatly, and stacked them in a basket. I can imagine her, at the end of a long day, cutting the scraps into squares or diamonds or hexagons, until she had enough to piece a quilt top. I can imagine her sitting by the stove, stitching the pieces together by hand, by the light of a kerosene lamp. The saving and sewing were a lifelong occupation. I know this because her scrap basket–containing neatly-cut mint green background squares and diamonds of solid reds and turquoises or hot pink with yellow polka dots, along with several half-completed squares for an eight-pointed star quilt–was beside her nursing home bed when she passed away in 1971.

As near as I can figure, my grandmother probably made between 80 and 100 quilts in her lifetime—all different; all beautiful; and many of the early ones made from the scraps of flour sacks left over from other sewing projects, like making dresses and shirts for her children. According to Linzee McCray, in the 1920s, after feed and flour sack manufacturers realized that women were bleaching the lettering off of their fabric bags to make clothing and other household items from the cloth, they began to make the sacks from colorful printed fabrics. Laura Casely estimates that during the Great Depression, over three and a half million people “were wearing clothing and using items made from flour sacks.” Scraps as small as two-inches square could be pieced together in a variety of patterns to make quilts, clothing, and other useful items like aprons and dresser scarves or decorative coverings to prolong the lives of chair arms or protect chair backs from my grandfather’s hair oil. Some people stitched small salvaged circles of fabric into gathered rounds, called yo-yos, and used these not only to piece quilt tops but also to make tablecloths and dresser scarves as well. Whole flour sacks, unstitched and flattened out, might also be hemmed to make tablecloths. My grandmother also used a bleached clover seed sack as a “dough cloth,” which she would sprinkle with flour and use for rolling out pie crusts or biscuits or tea cakes.

In addition to the feed and flour sacks my grandmother used for clothing, quilts, and household items, she also chose not to waste other things. For instance, she used scrap cotton (the dregs or pieces left behind in the field after picking was complete) to make the batting for her quilts, and the county cooperative extension service taught her to use dregs to stuff homemade mattresses for their beds.

When money was scarce, as in the Great Depression, creative and frugal homemakers like my grandmother made sure that their families did not want for clothing and warm bedding by cleverly turning every inch of a feed or seed or flour sack into something useful that did not, then, have to be purchased. “Waste not, want not”: the dictionary could have used my grandmother and thousands of other Depression-era farm wives like her to illustrate the meaning of this phrase.

Works Cited

Casely, Laura. “1930s Flour Sacks Featured Colorful Patterns for Women To Make Dresses.” Little Things. 8 Jan. 2018. https://www.littlethings.com/flour-sack-dresses/ ,

McCray, Linzee. “Feed Sacks: A Sustainable Fabric History.” 9 May 2011. Etsy blog. 8 Jan. 2018. https://blog.etsy.com/en/feed-sacks-a-sustainable-fabric-history/ .

“Waste not, want not.” McGraw-Hill Dictionary of American Idioms and Phrasal Verbs 2002. The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. 8 Jan 2018. https://idioms.thefreedictionary.com/waste+not%2c+want+not.