When I found out I was going to be spending an entire semester working towards a project involving Ancestry.com, initially, I was elated. I always wanted to know more about my ancestors, what they were like, where they lived, what they did for fun, and what kind of clothes they wore. I told my

grandmother about the project and she informed me of her attempt to chart out our family tree through Ancestry. Unfortunately, she isn’t the most tech savvy person, so she did not get anywhere; however, her efforts were admirable. She was incredibly helpful in giving me the names of about three generations of our family and I was able to start gaining some insight and information I could use for my project. To my surprise, that progress would be short lived. When Dr. Gardiner explained the assignment to us on the first day of class, she also gave a disclaimer. She told us if the person we were researching was a woman or a minority it could be difficult to find useful information on them. This is due to the awful way women and minorities were treated in the past, causing them to be disenfranchised and underrepresented in censuses, historical records, and all of history in general. I am thankful I did not leave empty-handed and was able to gather a little information from Ancestry and from some family members of mine. However, it took substantial amounts of time and frustration to gather that limited amount of information, and I had to watch as most of my white classmates found an abundance of information on their ancestors.

It is important to me that I tell the story of Alonzo Vickers, my great grandfather, to memorialize him and his legacy. Furthermore, I want to highlight my own frustration and the struggles I went through to gather the limited information.

Alonzo Vickers was born on May 3, 1892, in Lawrenceville, Alabama. Not much is known about his experiences as a child, but I do know that the highest grade he completed was 2nd grade. Furthermore, I found out from my great aunt Daisy Vickers (Alonzo’s second youngest daughter) that his parents were sharecroppers and their parents were slaves.

Alonzo would go on to become a sharecropper and farm laborer himself. The main crops Alonzo and his family picked were cotton and peanuts. Daisy told me the importance of being careful and precise when picking cotton, because it was sharp, and you could cut yourself. Not only would you be injured, but if your blood stained the white cotton then it became useless. She also told me that our ancestors were exploited by and worked for white men for many generations, originally as slaves and then as sharecroppers. It was typical for children to begin working in the fields around the age of five or six, at the latest seven. From slavery to the Jim Crow laws, the negro experience was one of endless exploitation, discrimination, and frustration.

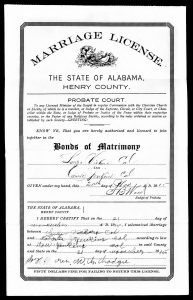

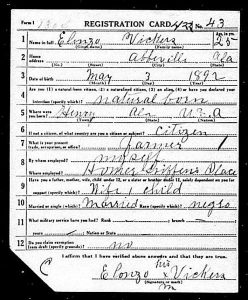

Alonzo first appears in the 1910 Census, as a seventeen-year-old farm laborer, unable to read and write, and living with his seven siblings. His brother Isaac Vickers is the head of household. He would soon meet his girlfriend, Carrie Jenkins, and they would get married on Sunday, November 21, 1915. On June 5, 1917, Alonzo registered for the World War I draft at the age of twenty-five, as a resident of Abbeville, Alabama—where I spent my middle and high school years. As my grandmother, my great aunt Daisy, and his draft registration card would suggest, Alonzo was a tall black man with a slender build, and he was bow-legged (Skipper). I learned about one of his children, Lonnie Vickers, who was six feet tall and weighed 165 pounds. I am also six feet tall and weigh about 160 pounds, so I imagine Alonzo shares a similar body type to Lonnie and me. Interestingly, this is the latest piece of information I found about Alonzo, as his named is spelled “Elonzo” on his draft card, which is why this document escaped me for so long.

On the 1920 Census, Alonzo’s name is spelled “Conzo” Vickers. The census also reports his marital status as single but lists Carrie Vickers as his spouse. He is the head of his household and he and Carrie now have two daughters, including my great grandmother Rose, and a son, Raymond (sometimes written as Waymon). Alonzo still serves as a farm laborer and he has learned to read but is still unable to write. I envision he spent most of his days out in the field picking cotton and peanuts as sun shines high in the sky. I imagine Carrie worked in the field, took care of the children and the household duties women were responsible for during the time, such as cleaning the house and making sure the men had a meal ready for them when they arrived from the field. These traits must be hereditary, because the women in my family are hardworking, show constant care for others, and are constantly overcoming and persevering the obstacles of life. The women in my family are also wonderful cooks, so I like to believe Carrie is where that all started. Alonzo more than likely ate wonderful meals daily.

Alonzo and Carrie spent much of their time procreating: during the 1930’s, they welcomed six more children: Andrew, Mildred, Hattie, Lonnie, Earnest, and Daisy Vickers. Alonzo also went from being a farm laborer to a farm owner, working on his own account. While he was still renting his home and did not own a radio set, he was now a farm owner and able to read and write.

Along with the 1930s came the economic woes of the Great Depression. While millions of people were affected by the Great Depression, negroes experienced the worst of it—especially the ones in the south. Negroes were often the last hired and first fired (Klein). They also still had to deal with discrimination and racist actions and behaviors like disenfranchisement, Jim Crow laws, and the intentional lack of funding and resources aimed to help negro citizens. I try to imagine the obstacles and struggles Alonzo and his family had to overcome, but I don’t even come close to what they truly felt. While he was a farm owner, having to feed seven children, his wife, and himself had to be a difficult task during the Great Depression. I picture Alonzo and his family working endless hours to make ends meet and taking drastic measures to make food and drinks last as long as possible, like limiting food and drink intake. While Daisy was born after the Great Depression, she said that I was right about the endless hours of work. Fun, playtime activities were limited and rare. Daisy told me that if they saved enough money, they could take a trip to the movies. Alonzo, his family, and neighbors might also play cards. Since I was a boy, I can remember my grandmother, her siblings, neighbors, and family friends gathering and playing cards and gambling for hours on end. According to her, this has been a family tradition for generations, so Alonzo and his family probably played cards, too.

According to the 1940 Census, “Lonzo” and Carrie would successfully have two children during the Great Depression—one of them being Daisy. They would also lose one due to miscarriage. The Great Depression had came and went–and then World War II–but the biggest post-Depression event for Alonzo and his family was buying and moving to a new farm in Richards, AL. Alonzo worked as hard as ever, a trait that runs in the family. The census reports that he worked a total of fifty-two weeks in 1939 and worked forty-eight hours a week prior to the census date. I imagine with most of his children being of age to work that he was able to lighten his workload a tad. According to Daisy, they would hang onto this farm for several years. Daisy eventually grew old enough, so she not only worked in the field, but also had to cook and clean. Alonzo worked until his body grew old and weak. He would then settle down in Newville, AL, until his death in late April of 1980.

From my own personal research and the stories from my grandmother and Daisy, this is all I know about Alonzo Vickers. I began this project with high expectations, hoping to find out about my family’s history and as the project is ending, I cannot help but to feel like there could have and should have been more for me to find out. However, due to lack of information, I am left in a state of bittersweet frustration. The lack of information can be attributed to how poorly negroes were treated throughout the 20th Century and how they were seen as “less than” or a type of “other,” not worthy of further documentation. It can also be attributed to Ancestry’s paywall, limiting access to my family’s records by charging an incredibly high price for a membership. If I have learned anything in life, it is that wealth is inherited more often than it is gained. There are probably a plethora of white families that can pay for memberships and find substantial information on their family’s history. The paywall skews the system against poor people, but especially poor minorities. The deck is stacked against people who faced discrimination and oppression in the past, and the effects can still be felt today. In the process of looking for Alonzo, I think I came across the slave family that owned my ancestors and gave them their slave names. There were several white people whose records showed up with the last name Vickers, living in the same area as all my ancestors. The oldest record I found of the white Vickers family was the 1860 Census of Hatcher “Vicers,” who had a wife Lucy and four children: Jesse, Drewey, Sarah, and Babe. The Vickers surname first appears in the family’s 1870 Census. I looked through more of their records and there is an abundance of information on this white Vickers family on Ancestry.

This has been quite the journey, consisting of a rollercoaster of emotions. All this excitement, discovery, and frustration has taught me the value of not letting ancestors pass on without learning their stories. Alonzo Vickers is an important man in my family’s legacy, yet all that remains of him are censuses and two other documents. I am grateful for what I did find, but there is more to my family’s legacy than a few censuses, draft cards, and death certificates.