My grandmother, Phyllis Mostellar (or as we, grandkids, called her, Lizzie) knew him the best. Philip Williams, my great grandfather, was her father, and she was his only child. And maybe that was how I came to be a part of such a large family, for my grandmother enjoyed every minute of her busy household, hosting the family every Christmas, Easter, and birthday possible. My mother was Lizzie’s third of four girls, making me only one of eleven other cousins: Jane with 3 (two boys and a girl), Anne with 1 (girl), Mom with 3 (Me, and my two sisters), and Kate with four (two boys and two girls). My mother was also named Phyllis, so it was fitting the family name was passed to me. In this way, I always felt like my grandmother and I understood one another like kindred spirits. As well, I was only alive for about six months before my great-grandfather passed away, barely getting to meet him. It was as if he was if a spirit of my past. And thus, I saw she felt it her duty to teach me what kind of a man Philip Williams was. What kind of a man I could be, carrying his name.

When you are in the middle of eleven kids it is easy to feel lost, yet Lizzie always found time to talk. Every other week, she would pick me up from Mary B. Austin Elementary School to go to Carpe Diem, a local coffee shop in Mobile, AL, across from the Spring Hill College campus. There Lizzie ordered hot chocolate for me and a pot of hot water for herself; being steeped in Great Depression frugality, she would be foolish to leave home without a couple of bags of Earl Grey in her purse. Then we would sit at a table by the window as I would ask about her childhood and her father Philip’s life. I already knew the joys of getting lost in a tale, but it was during these outings with my grandmother that I began to develop an interest in history. As well, my mother taught the subject at Murphy, the high school downtown, so I thought it curious we did not know more about our family’s past. Lizzie would tell me how Philip had an older brother named John Philip, who passed away from rabies three years before Philip was born. And how his parents John and Harriet chose to preserve the memory of their deceased son by naming their new one Philip. The tales were like modern-day legends, so when I first heard this, I thought it peculiar; however Lizzie claimed it was normal in the south at the time. To me it seemed almost like a breach of a life-contract, like the family was harboring a ghost. Which makes me wonder how Philip felt?

She told me how Philip attended the Duncan School, a Nashville elementary-preparatory school, in the early 1920s, and about how his father gave him a dollar for lunch on the way to school at the start of each week. One Monday, Philip skipped school and spent his entire dollar on candy and a movie. The next day, when John dropped Philip at school, he asked Philip to make sure he had his lunch money. Philip, overcome with sleepless guilt, let out a quivering sigh and confessed. John looked down, clearly disappointed. He took out his wallet, pulled out another dollar, and held it out to his son. However, before handing the dollar to Philip, John explained to his son some people do not see nearly as much money in an entire year. The lesson stuck: I can hear it radiating through my grandmother’s story, while also teaching me the importance of money. Interesting stories like these amused me, and though the morals may have initially eluded me in my youth, Lizzie was always two doors down the street to remind me.

Some histories in the South are known and unspoken because of the veil of shame that we have cast upon the region–in the wake of development from post-Civil War through the Civil Rights movement and continuing into the present. To put it plainly, since the abolition of slavery the south has been too ashamed, or afraid, to address the subject and its immorality. As a child, I eventually learned about relatives who fought in the Civil War, and of course like many from the South, I knew they were not on the “winning” (i.e. good) side. As if civil wars ever have “winners.”

Philip Williams was one of the last of the Overton family to live in Traveler’s Rest, a large farm located outside of Nashville. Nevertheless, with large southern plantations come ominous beginnings. Traveler’s Rest was built in 1799 by Judge Overton Williams, his great great-grandfather, a banker, lawyer and eventually served on Tennessee’s Supreme Court. However, Judge Overton was also noted as a law partner, and close friend, of President Andrew Jackson (Tennessee Encyclopedia). Thus, it would be pertinent to mention through research of the farm, Traveler’s Rest housed around 80 slaves prior to the Civil War. This information is only worth mentioning to set the idea of how Philip’s family’s financial position was before the Great Depression, along with the advantages “afforded” to his familial position in the south. As well, when receiving this information in recent interviews with Lizzie, she advised against sharing said information, only reaffirming this ‘veil’ of shame that became increasingly apparent. This was the first real confirmation I ever heard from her, but sadly I was not too surprised. In 1929 at the dawn of the Depression, Philip’s parents John and Harriet finally sold Traveler’s Rest, leaving the Overton family’s ownership since the founding. Farm prices in Tennessee already began falling after WWI and remained low throughout the 1920’s, therefore it is reasonable to speculate Traveler’s Rest did not sell for much (“The Depression in Tennessee”). However, according to Lizzie, the buyers never moved into the house because of “the ghosts of Judge Overton” (“Interview with Phyllis Williams Mostellar”).

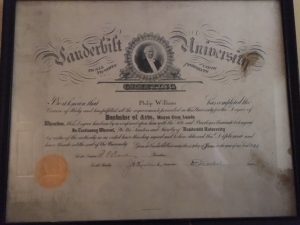

Regardless, what I really wanted to understand was why my family did not talk about this? Was it shame? Shame of familial sin? Such may be understandably so; however, it could be a continuation of the trend of systemic oppression present in the South, created after the African-American fight for Civil Rights and Integration. It is arguably so that these problems thus allowed Philip opportunities not afforded to other people, as he was able to attend Vanderbilt College

during the first half of the Depression. But perhaps this could be an explanation for his focus toward his work, his wife, and his daughter (and his eventual four grand-daughters) as opposed to pondering on his family’s shameful beginnings as plantation slave owners.

Excuse me. Our family’s shameful beginnings.

At times it is easy for us to recuse ourselves of our father’s wrong-doings, but what if the South rebuilt the region with a tone of teaching our children history based in these horrific mistakes? It is easy for the South to forget their sins when it goes unmentioned. More than likely, Philip did not stay silent about his family’s history through shame, but simply through the southern societal norms. Thus, explaining the slow change of pace for peace and progress in the region.

In graduate school, Philip realized he would make a terrible lawyer, dropping out of Columbia in the first year. Fortunately, he quickly learned he could make a much better businessperson, landing his first job working as a sales associate for the Continental Can Company in 1936, in Memphis. The job with the CCC provided him with employment for two years. However, it was at this point -in the last half of the Depression- Philip underwent the most life-altering changes thus-far. He married Martha Jane Boyd (known to her grandkids and great-grandkids as Mama Jane) in September of 1936, impulsively on a visit to her in Mississippi.

The marriage was unbeknownst to the Williams–and perhaps under the pressures of Martha Jane’s mother and aunt. Then, in 1937, Philip and Martha Jane experienced the most change in either of their lives, especially for the Great Depression era. On November 19th, a healthy baby girl, my grandmother, was born and Philip and Martha Jane’s world changed forever.

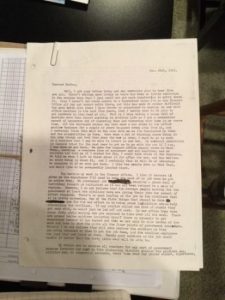

Yet, with this change, Philip sought opportunity. The following year, Philip was hired to work for the Burroughs Company, in Jackson, TN, selling adding machines. They retained residence there until 1942 when Philip enlisted in the army, and Martha Jane and Lizzie moved back in with Martha’s sister, Aunt Meada (“Interview with Phyllis Williams Mostellar”). Unfortunately, there is not much else I was able to retrieve for this time because Philip was still young and fresh out of school, and Lizzie was still an infant. And as Martha Jane and her sister have passed, first-hand sources from the Great Depression are nearly gone, aside from Lizzie’s birth and infancy. Nevertheless, from his letters to his mother and Mama Jane, it is easier for one to gain a sense of how he thought and rationalized certain steps of his life. As if he had an old soul. Philip’s positions changed in the service as he took on the role of financial management and system operations trainer. Reading some of the letters Philip sent while stationed in North Africa, he talked to his mother about his time registering accounts and working with the adding machines. He talked about the time away being beneficial for him to learn how the adding machine works, completely, for when he went home and returned to the Burroughs Company. Even though his time overseas was different, he reflected on the importance of the enlisted soldiers. He also reflected on how much he enjoyed learning about the workings of the adding machine; along with how he and 12 other staff soldiers were tasked to train 20 women. He complains, adding in a misogynistic, if not unnecessary remark, and continues to write how he is fortunate to be able to work with the older enlistees, saying they complained far less than the younger ones. I was not sure if this was 28-year-old Philip trying to be funny, or just a sprinkling of the sign of the times.

From all I have been told Philip had a good sense of humor, and was quite clever, so I would not put anything past him (“Dearest Mother” letter).

After the war, Philip come back to Marth and Phyllis in Jackson, and went back to work for the Burroughs Corporation. They moved to Brownsville in 1945, located 26 miles out from Jackson, allowing Philip to commute to the Burroughs. He worked for them until 1967, when he has a brain aneurism at 53. However, he only stayed retired for two years before going back to work, because he was driving Mama Jane crazy from all the practical jokes around the house, according to Lizzie and my mother. Looking for work in a closer proximity, Philip went on to manage the Brownsville Savings & Loans for 10 years, before retiring for good at 65.

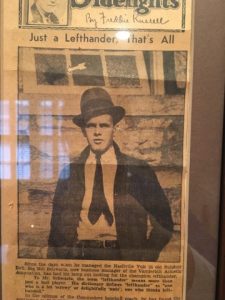

When asking my mother what Philip was like, she had plenty to say, which makes me imagine the kinship she felt with Philip was strong, like Lizzie and me. That kinship could be seen in the litany of fun facts and delightful anecdotes she had about him. She explained how Philip was a cheerful spirit. A chubby man, with a bald head, and a bright sense of humor. My mom explained how much he loved baseball, playing at Vanderbilt, and even being written about in the paper.

She told me about how Mama Jane would not let him drink, turning him into a “teetotaler” -– or somebody who only drinks tea. She told me how he would eat extremely slowly, in a clockwise direction around his plate, every meal. As well Papa would give her Tangerine lifesavers, because he said they used to calm him whenever he went to a new school. And finally, she told me about all their family visits to Brownsville to see Papa and Mama Jane. She said every time they would be packing to head back to Mobile, he would try to convince mom to stay in Brownsville. He would grab one of his old suitcases telling her, “Your parents have plenty of kids, they won’t even notice you’re gone.” It was as if he was always joking when he was with family and friends. I still think the funniest story my mom remembers is when she was a teenager, visiting during the summer. In her words, she said, “One time I was curling my hair in the living room and Papa was sitting around. Then he looked over to me and said, ‘I used to have hair like that, and I curled my hair every day” (“Interview with Phyllis Mostellar Knott”). Yet, he was no ghost to her. Like Lizzie to me, she is graced with the vivid memories from her time with Philip. Her stories were almost like myths being passed down through the word of mouth. Philip’s ghost transforms.

The man was too good, as if he was one of the few people with knowledge of some big inside joke. He figured it out. It was clear that my mother loved her grandfather completely and had a much similar closeness in spirit with her grandfather, as I have with Lizzie, even if not merely as close in proximity. He was a smart man, who acted as if he had the secret to life, and perhaps he did. A simple life as a businessperson in a quiet town? Light-hearted optimism? Who’s to know? But he lived a nice, interesting life and was from a weird southern family–the Overtons. Perhaps it was the Overton mysticism that made Philip a ghost in my eyes as a child. Or perhaps it was imagining a time so completely different than the way we are used to in the 21st century. Nevertheless, getting to discover more about him has allowed me to revere his hard-working nature, and charismatic whimsical attitude. He grew up upon eerie lands with ominous beginnings, but if he had a problem with the “ghosts” of his ancestor, then he set them aside when he moved away from Nashville But nevertheless, he chose to look toward a brighter future for a family of his own. He lived to be 79, and he is remembered fondly. Thank you, Philip Williams … I mean “Papa.”

Works Cited

- Brown, Theodore. “John Overton.” Tennessee Encyclopedia, Tennessee Historical Society, 1 2018, tennesseeencyclopedia.net/entries/john-overton/.

- Knott, Philip Williams. “Interview with Phyllis Mostellar Knott.” 5 Apr. 2018.

- Knott, Philip Williams. “Interview with Phyllis Williams Mostellar.” 15 Mar. 2018.

- William Hardy. “The Great Depression in Tennessee.” Microsoft Word – TN Great Depression.doc, 22 May 2008, 11:11:36 am, teachtnhistory.org/File/TN_Great_Depression.pdf.

- Williams, Philip. “Dearest Mother.” Received by Harriet Overton Williams, 21 Dec. 1942, Nashville, TN. sent from station in North Africa.