There’s one thing that I tangibly have. Not like memory or a love letter or a eulogy. Something that I can pick up and hold. It’s a stuffed toy from Disneyland and it had a special place on my bed until I left for college. It is a stuffed Grumpy from Snow White.

The story goes like this: when I was born, my great-grandfather Edward Dean Stetson told my mother that his name was too much of a mouthful for a baby girl to say, so I should call him Grumpy. So, I did.

When a person goes, what are we left with? How do we remember a person we hardly knew?

When a person goes, how do we write something about them that is both small and simultaneously important enough to forever memorialize them?

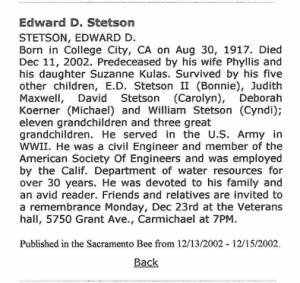

This is Edward Dean Stetson’s obituary.

I guess that’s how you do it.

This was him, my great-grandfather. His wife. His number of kids, grandkids, and great-grandkids. He served in the Army. He was an engineer. He was devoted to his family. I stopped in my tracks when I read this because this is so different from all the other facts included about him; he was devoted to his family. How do we portray this? We can simply tell people, I guess.

But, he was so much more than this small paragraph, and here I am, seventeen years after his death, reading through eulogies and trying to figure out how to write something good enough to depict how amazing of a man he truly was.

Trying to pick apart what we have left to determine what I can use to write a story about someone who left such a deep impact on those he encountered, someone who, I’ve been told, is too good a man for words.

While I’m struggling with this, something hits me. He wouldn’t have had this problem–making something amazing of what we have left of him. My grandpa said about his dad in his eulogy: “Dad, he took what life dealt.” He included in telling the audience all that his father did for him and his family, that “he never once complained, never seemed to get discouraged.”

Throughout his entire life Grumpy went on using what he had to make the most of every situation. Even during the Depression, when so many people in so many places had such little left, it’s almost as if he didn’t even care if something was ever missing.

When the Depression hit, he was thirteen years old. When I was thirteen years old I was extremely NOT self-sufficient. But he, he could do anything. He lived on an almond ranch right outside of Arbuckle, California, with his mom, dad, and older brother Willard. Soon enough, the ranch would nearly be all his responsibility.

The law in California stated that if there was a man in the house, the household could not collect welfare or any sort of government assistance. So, in the best interest of the whole family, his dad left home and went to Utah to run cattle as a cowboy. How very western of him.

This left my Grumpy and Willard to be the ranch hands. So, for the next five years this ranch was his life.

I obviously wasn’t around then and there was no way for me to find out what a day on the ranch would exactly look like, but if I could speculate, this is what I would imagine:

It’s about 5:30 on an August morning and the sun begins to rise, the roosters out in the barn crow, and my great-grandfather knows it’s time to wake up. Almond harvest season usually spans August-September, so he knows it’s going to be a long day, but he wants to get moving before the heat sets in.

He gets up, goes into the kitchen, makes breakfast, and heads out onto the ranch. He walks up and down between the rows of almond trees, admiring the quite-literal fruits of his labor before he gets to shaking the trees.

To harvest almonds, almond ranchers must lay down tarps and shake the trees to knock the almonds to the ground. After all the almonds fell that could be shaken out, they would take a looooooong pole, reach up into the tree, and try to knock out the rest of the almonds onto the tarps.

After harvesting the almonds, there were a few more steps before they would be ready for sale. An almond, as it grows on the tree, has a soft, powder shell called a hull. The hulls must be removed before they can be sold.

I would imagine, after harvesting the almonds from the trees in the mornings, my great-grandfather would spend the afternoons removing the hulls with a machine that he created to help him do it. People from neighboring farms would drive over and pay him to use this machine to remove the hulls from their almonds, too. A little extra work, but added income during this time of hardship was a huge bonus.

I’d imagine he’d do this until the sun was down so far below the horizon that he couldn’t work anymore. My grandfather told me that when he was building their family home, with his own bare hands, he would work hours into the night until he just couldn’t anymore. So, I’d say it’s a safe assumption that he probably was this way as a teen, too.

After the sun went down his gears would shift into family time, something that has been always been a priority to him. “Devoted to his family.” Included in his obituary–something so true to his being that it had to become a part of what was left of him, memorialized forever as someone devoted to his family.

My Aunt Carolyn told me a story that she remembered Grumpy telling her. She said she doesn’t remember him talking about going into town much, but she does remember a few things that he did for fun. He used to wrangle up feral cats and feed them in the barn on the ranch. The other thing that stuck out to me was a particularly funny image.

Imagine this:

On summer nights when the sun would go down, Grumpy and Willard would sneak to edge of their ranch property and hop over the fence into the neighbor’s yard. They would go row by row and crack open watermelons so that the deep pink, juicy centers were exposed and eat the hearts out. They would go up and down the rows having a feast like kings on the neighbor’s watermelons.

This is how things were for the first half of the thirties. Once 1935 hit, everything changed. Grumpy was eighteen and it was time to go to college. He enrolled in college up in Sacramento and studied Civil Engineering. A fitting course of study for someone who had made a machine to help get the hulls off the almonds he ranched.

He spent the rest of the 30s commuting between Sacramento and Arbuckle so he could both study and work on the ranch.

After studying civil engineering, he went on to work for the California Department of Water Resources. He did this for 30 years.

On March 4th, 1939, he eloped. He met a young woman name Phyllis Runkle in college. The two of them were married for 61 years and nothing but death could keep them apart.

Soon after they were married they started their family and 58 years later came me.

In 1944 he went to war. A boat took him out of Benicia, California, and over to South Carolina. Here he was drafted into the Army Corps of Engineers.

After returning home, he continued his balancing act of work and home, never once neglecting one of the two. He spent years toggling between surveying the California Mountains and water runoff patterns and going home to build the family house, with his bare hands.

From his eulogy, my grandfather says:

“And he did it, got his degree, finished the house, and still had time for Boy Scouts, 4-H, little league and all the other demands family brings. And he never once complained, never seemed to get discouraged. He was a man, and showed us what that meant.”

In a phone call with my grandpa, he referred to his dad as the “iron man.” Said he “couldn’t believe his stamina, perseverance, and just plain hard work.”

So, this is how he will live on. These memories, these words, and now my words, here, on this website.

This is what we have left.

To everyone who comes here to read this, I hope I have done him justice. The man who could always makes the best out of every situation (read: he could make anything wonderful out of what he had left).

This now is what we have left.

Works Cited

Garibay, Cassandra. “Long Days Are Typical for Almond and Walnut Farmer.” Central California Newspaper | Madera Tribune, Central California Newspaper | Madera Tribune, 24 Aug. 2017, www.maderatribune.com/single-post/2017/08/07/Long-days-are-typical-for-almond-and-walnut-farmer.

Stetson, Carolyn. Personal Interview. 8 Feb. 2019.

Stetson, Edward. Personal Interview. 25 Mar. 2019.