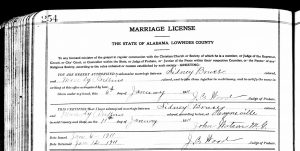

Mandy [Millie] Brown, my maternal great-grandmother, was a homemaker who worked hard everyday to provide for her family. Although she didn’t often contribute to working outside of the house doing farm labor with her husband, she was the queen of her kitchen and loved making pies. Born in 1884, she married her first husband, Sydney Bruce, at the age of 27 on January 6th, 1911; he was a farmer in Montgomery County, Alabama . Two short years later, by the age of 29, Mandy divorced Sydney and married my great-grandfather, Peter Brown. Together, Mandy and Peter Brown shared their lives working as sharecroppers in Lowndes County, Alabama, where they grew cotton, field peas, and corn.

There they also extended their family having four boys and one girl; Ed, Thomas, Peter, Abram, and Lucille Brown (my grandmother).

While reading the chapter “King Cotton” in Dale Maharidge and Michael Williamson’s And Their Children After Them, it was interesting discovering that my great-grandmother and great-grandfathers’ occupations as sharecroppers were classified as the lowest level of tenant farmers. As a result of their low income, they didn’t have enough money to own tools. They were referred to as ‘halvers,’ meaning that they “had to give over a much greater proportion of the crop than tenants did—half their corn and cotton, an additional amount to cover their portion of the fertilizer, and an average of 40 percent interest,” (“King Cotton” 14). After the Emancipation Proclamation, it was recorded that “white tenants in the cotton states increased by 200,000,” while “negro tenants decreased by 2,000 families,” thus supporting the evidence that my ancestors were amongst the 51.6% of sharecroppers who remained in the south following the end of the Civil War (“King Cotton” 13). Since Mandy and Peter Brown were both children of recent slaves, they didn’t accumulate enough money to travel up north with five children and no transportation. Mandy saw this as an opportunity to transform her passion for baking pies into an occupation that provided for her family. While her in-home pie business was booming prior to The Great Migration, her pie sales quickly came to a halt when her neighbors moved up North in search of work. Their family was back to struggling with low income and Mandy and little Lucille were forced to help work on the farm to help the men raise crop until she got the idea to expand her pie business into other neighborhoods.

During my great-grandmothers’ lifetime—Mandy strived to accumulate more money contributing to the tools and mules used to create better crop on the farm they worked on. Using the pie recipes created by her mother Lily [Ella] Gibson— a former slave living in Egypt, Alabama— Mandy and my grandmother, Lucille Brown, would work together making pies: sweet potato, apple, and pecan

Whenever Mandy made pies she used her favorite three pie pans made up of thin aluminum. Using the recipe passed down from three generations, Mandy followed each step diligently, baking pies using nine inch thin aluminum round pans each having dents telling different cooking stories of Lucille and her mother working in her kitchen. Mandy never threw the pans away, she would wash and reuse them for the next cooking day. Mandy, in her lifetime made and sold hundreds of pies to neighbors and fellow sharecroppers, eventually passing the recipes of the sweet potato, apple, and pecan pies down to her daughter— my grandmother Lucille Brown.